Endeavors, the online magazine of research and creative activity at UNC, recently featured the work of Dr. Bob Duronio and iBGS.

The genome of a fruit fly is strikingly similar to that of a human — so much so that scientists have been studying these tiny insects for over 100 years, in search of treatments for diseases like spinal muscular atrophy and neurological disorders. UNC geneticist Bob Duronio is one of those scientists.

“It begins with curiosity. Curiosity about a process. And then a question about that process. And then a hypothesis that will lead to an experiment that will provide results and data to interpret. What I love about this process is that my hypotheses are often wrong. And that’s really exciting — because no human being is smart enough to understand biology at a level of molecular detail where their hypotheses are always right.”

-Bob Duronio, director of the Integrative Program for Biological and Genome Sciences

“Beautiful.”

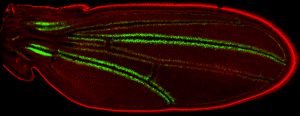

Robin Armstrong adjusts the focus on her dissecting microscope. Iridescent ovals float in the ether, clumped together, stark against a black backdrop. They look like the little, individual fibers that comprise the flesh of a grapefruit — long and plump and juicy. Though this grape-shaped bunch is far from produce, it’s fitting that they belong to a fruit fly. Armstrong is examining its ovaries.